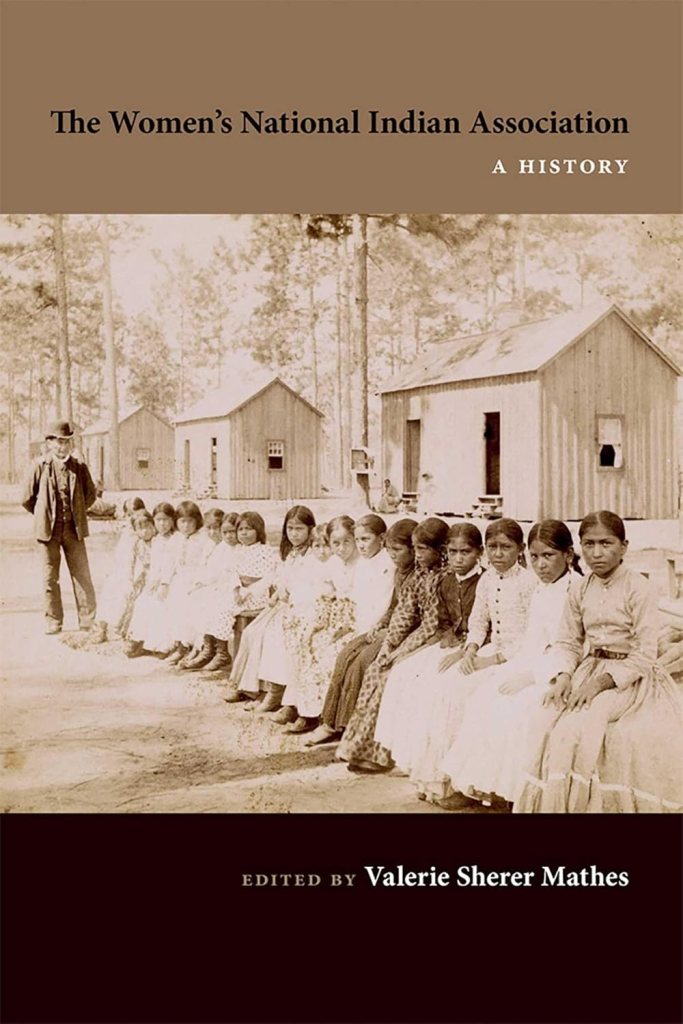

In October 2013, I had the honor of serving as the respondent for a conference panel on the Women’s National Indian Association (WNIA). The organization was founded in the late 1870s to advocate for Native women through Christianity and assimilation into white American society. Before the conference, I read papers by Valerie Sherer Mathes and Helen M. Bannan. Below are my remarks on the essays, which I delivered at the Western History Association annual conference (Tucson, Arizona). Two years later, the authors published their papers in Mathes’ edited book, The Women’s National Indian Association: A History, by the University of New Mexico Press (2015).

*******************************

Seeking the Native Voice in the Women’s National Indian Association

by Matthew Sakiestewa Gilbert

It is an honor to be here this morning.

I want to give a special thanks to our panelists, Valerie Mathes, Helen Bannan, and, of course, my friend and colleague, Margaret Connell Szasz, who helped organize this gathering.

There is so much that can and should be said about the papers, and yet I have purposefully kept my comments brief.

I have been asked to focus on the “Native voice” and its role and importance in historical narratives.

Historians who work hard to include the Native voice in their works realize that Native people have something important to say about their own histories.

They realize that Natives of the past once demonstrated great agency, and that their individual and collective experiences matter when they retell their stories.

We know that some historians are often content to simply peruse the literature for glimpses of the Native voice.

And when their search comes up empty, they say to themselves: “Well, if I can’t find it in a book or article, then the Native voice must not exist.”

This, as you know, is far from the truth.

As we have heard this morning, it’s been difficult for historians to uncover the Native voice in the larger history of the WNIA.

But does this mean that the Native voice (at last within this context) does not or has never existed?

Consider for a moment the several historical newspapers of this period that reported on the WNIA, and how many of them (at the very least) hinted at the Native voice in their articles.

For example, at the Association’s fifth anniversary gathering in Washington, DC, in March 1887, a Washington Post reporter noted that “The history [of the WNIA] is supplemented by passages from the letters of the Indians who have been thus benefited [by the WNIA] and is to be published by the society.” (The Washington Post, March 5, 1887, p. 2).

Did the Association publish these letters (presumably in The Indian Helper) as the Washington Post reporter suggested? If so, and if the letters are available to researchers, what might historians gain from these accounts?

Other newspaper accounts report on so-called civilized Natives who addressed the WNIA at several of the Association’s annual “Branch” gatherings.

For example, at the Washington Branch of the WNIA’s annual meeting in May 1892, a reporter for the Washington Post noted that the Omaha physician Dr. Susan La Flesche, a “graduate of the Philadelphia Medical College for Women,” was scheduled to “address the meeting.” (The Washington Post, May 20, 1892, p. 4).

What did this prominent and very well-educated Omaha woman say in her address? Perhaps we will never know. But the historian in me wants to believe that there is an account of it somewhere.

One of the more powerful accounts of the Native voice and the WNIA took place in June 1884.

At this time, the WNIA had called together a meeting at the First Baptist Church in Philadelphia for its members to listen to Nez Perce Chief James Reuben talk about the wrongs of the U.S. government against his people.

A newspaper reporter for the Philadelphia Times noted that at the meeting, Reuben “gracefully took his stand behind the pulpit and, gazing cooly upon his audience, deliberately arranged a number of papers with which he had come prepared to fortify his cause.”

Here is how Reuben began his address:

“If only I could know your hearts and know how to address you and what things you are interested in, I could shape my address so as to please you all. I will speak, however, only upon the relations of my people and the Government.”

Reuben then went on to give his audience a brief history of his tribe and told of the many treaties that the U.S. government broke with the Nez Perce. He asked the WNIA’s help in convincing the government to allow a group of 250 Nez Perce, who at the time had been forcefully removed to Oklahoma, to return to their homelands in present-day Idaho.

“My heart is true to you as a Red Man,” he said to members of the WNIA who had gathered, “and you will find that the red man is just as honest as the white man. If you succeed in this object, I congratulate you in the name of God, and I believe you will succeed. The Indian is a man and ought to have all the rights of a man.” (San Francisco Chronicle, June 16, 1884, p. 2).

In the late 1800s, Rueben’s voice mattered to the WNIA. And his voice ought to matter to us today.

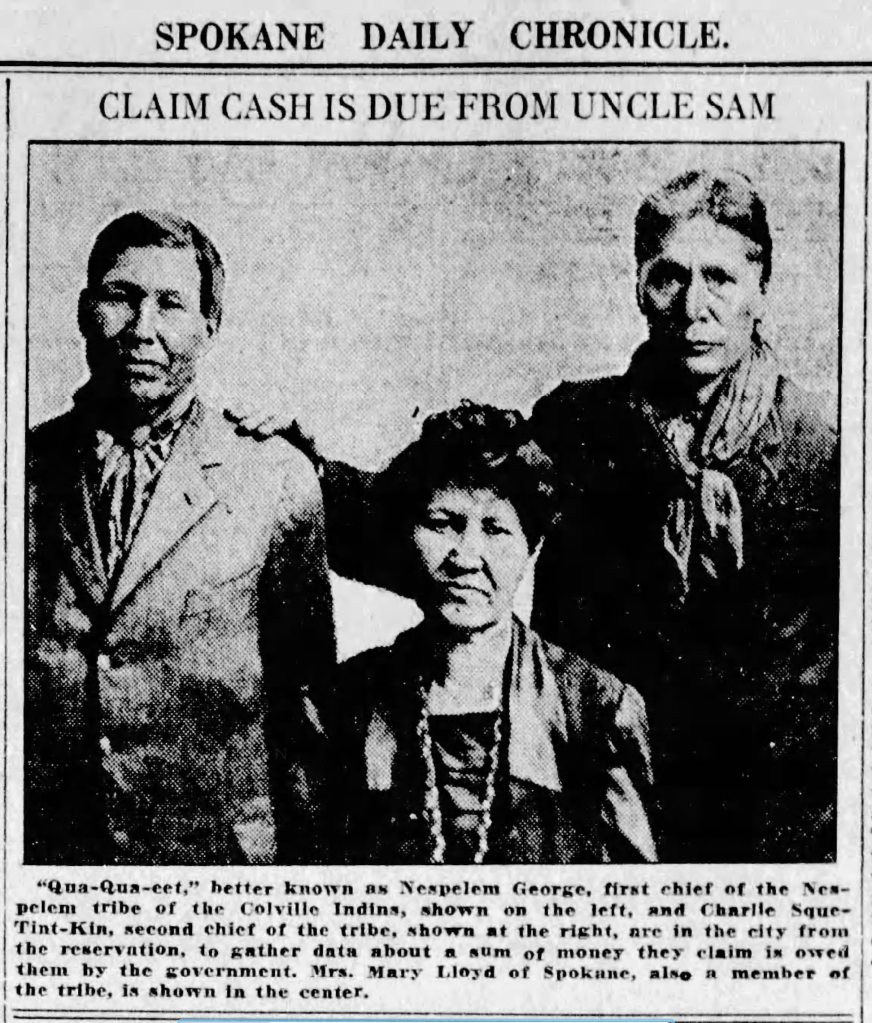

Furthermore, I am curious to know whether the WNIA motivated Native women in the 20th century to create their own organizations and clubs. We know that by the mid-1920s, hundreds of Native women from twenty-eight tribes came together to form The Eagle’s Feather Club in Spokane, Washington. Did these Native women create this organization in response to years of white women telling them how best to act and think?

I find the two organizations similar, but also very different.

Listen for a moment to Mary Lloyd of the Spokane Tribe in Washington (also adopted into the Colville Tribe), who also served as one of the Eagle Feather Club’s early presidents: “We pledge ourselves loyally to aide one another and all Indians to further ideals as first Americans, for developments and improvement. We pledge one another to drop all of our differences, and unite in a common friendship, cemented by this association, to work for our common good, and the betterment of all.” (Boston Daily Globe, August 5, 1926, p. A21).

And finally, I want to very briefly encourage or suggest that our two presenters spend more time examining Native (tribal specific) understandings of maternalism, and how this clashed with and complemented the political aspects of white American maternalism of the late nineteenth century.

There are ideological, cultural, and religious differences that are worth interrogating, and doing so (in addition to the inclusion of the Native voice) will only strengthen two already outstanding papers.

Kwa-kwa