In October of this year, University of Arizona President Robert Robbins sent me and all campus employees a memo informing us that due to a recent Executive Order from President Biden, which requires “institutions that contract with the federal government” to comply with guidance from the Safer Federal Workforce Task Force, we must either be “fully vaccinated for COVID-19” or receive a “religious or disability” accommodation by December 8, 2021.

A month prior, and knowing that this mandate would likely be forthcoming, I sent two campus administrators, N. Levi Esquerra and Karen Francis-Begay, a letter of concern and noted that such a mandate “may go against” Native people’s “religious or cultural beliefs, and may go against the counsel of their elders or healers in their communities.”

In my letter, I also noted that the university’s decision to approach the COVID-19 situation from a purely Western scientific perspective, did not take into consideration the “long and painful history that Native people have endured involving the federal government’s mandatory inoculations, forced sterilizations, and racism and discrimination toward Natives under the guise of ‘public health.’”

The below comments, which I gave during the School of Geography’s annual “My Arizona Lecture Series” event, revisits this letter and provides additional historical context to my concerns. I end my comments by offering four recommendations to President Robbins and other UA campus administrators, which I hope they will consider.

(I have slightly revised a portion of my introduction to better fit the flow of this post)

*****

“All Native Voices Matter: Addressing the COVID-19 Pandemic from the Field of American Indian Studies,” a lecture delivered for the “My Arizona Lecture Series,” School of Geography, Development, and Environment, University of Arizona, October 29, 2021.

Thank you, Dr. [Jeffrey] Banister, for that very gracious and kind introduction. And a big thank you to the Committee who organized this event.

I also want to welcome and thank everyone for being here today.

I know that this is a busy time of the semester, and yet you are here, and I want to thank you for that.

When Dr. Banister invited me in August to be this year’s “My Arizona Lecture Series” speaker, I was, of course, thrilled and honored by the invitation.

As an enrolled member of the Hopi Tribe from the northeastern part of the state, the idea of “My Arizona” is certainly meaningful to me, and my connection to the larger Hopi community is what grounds me in my talk this afternoon.

At the time of Dr. Banister’s invitation, I had just sent an email of concern to two campus administrators, N. Levi Esquerra (Senior Vice President for Native American Advancement and Tribal Engagement) and Karen Francis-Begay (Assistant Vice Provost for Native American Initiatives), regarding UA President Robert Robbins’ COVID policies and how those policies related to American Indians at the University of Arizona.

To better grasp the concerns of my letter, it is necessary for us to look to the past, which I believe will provide a critical lens to understand what is taking place at the University of Arizona in regards to Native people and its COVID-19 vaccine mandate.

A good place to start, I think, is with Native people themselves.

Prior to Europeans arriving on this continent, Native people dealt with diseases and other forms of sickness with traditional remedies. They made medicine from plants, performed ceremonies, and called on the spiritual world to help in their time of need.

When new diseases such as smallpox, which had been introduced to the Indian world by Europeans in the early 1600s, the people approached these diseases as they had others for thousands of years, relying on the practices of their medicine men and women, seeking wisdom from elders, and recalling lessons from the ancient ones.

Sometimes their traditional medicines brought the people relief from the devastating effects of smallpox, other times they did not.

For my people, the most well-known smallpox outbreak on Hopi lands took place in 1898 and 1899.

Mostly confined to the Hopi villages on first and second mesa, smallpox infected some 632 Hopi individuals, and killed 187.

Although the federal government had launched a campaign to inoculate 1,000 Hopis with the smallpox vaccine, only 412 people initially “submitted to the government’s vaccination program.”

The so-called traditional Hopis, still “clinging” to their old ways and ancient remedies, refused to comply with the government. Instead, they encouraged the people to rely on their Hopi methods, reject the white man’s medicine, and resist.

Furthermore, traditional Hopi individuals believed that smallpox entered their lands because the people had been neglecting the Hopi way of life, and embracing Western thinking and practices. In this regard, they understood smallpox to be a form of punishment.

The federal government, however, had little patience or sympathy for the Hopi resisters. Government officials forcefully removed them from their homes, burned their belongings, and arrested many of them.

Concerning this time in Hopi history, noted historian of southwest American Indians Robert A. Trennert once observed:

“The Hopi smallpox epidemic of 1899 was a costly, sad tribute to cultural misunderstanding. Because of a decade of insensitive forced acculturation, many Hopi leaders believed that any government attempt to promote their welfare was simply a trick to destroy their culture and beliefs. In response, they resisted and refused to cooperate. The Indian Bureau tried to save lives, but cultural insensitivity and the desire to graft medical treatment onto the boarding-school issue made cooperation impossible. The result was an unplanned, unavoidable disaster that did nothing to alleviate the traditional Hopis’ suspicions of white government and contributed to the widening rift between tribal factions.”

Robert A. Trennert, “White Man’s Medicine Vs. Hopi Tradition,” Journal of Arizona History, Winter 1992, p. 364.

Of course, the government’s campaign to inoculate Indian people, which furthered Indian distrust of bureaucrats in Washington, did not begin with the Hopi in 1899, but it existed (in various forms) several years before.

In 1832, for example, under President Andrew Jackson’s administration, Congress passed the Indian Vaccination Act which allowed funding for the federal government to vaccinate nearly 50,000 American Indians against the nation’s smallpox epidemic.

While one may be tempted to conclude that the federal government had purely noble intentions in forcing Native people to be vaccinated, the opposite was true.

In her article, “Lewis Cass and the Politics of Disease: The Indian Vaccination Act of 1832,” former AIS/UA Ph.D. student and Lecturer at UC Berkeley, J. Diane Pearson observed that:

“As the largest program of its kind in the United States, protection of American Indians from a deadly disease was the ostensible goal of the program, though other federal agendas provided the real motivation. There was no input from American Indians during the conception, design, and implementation of the program, and vaccinations were used to enable Indian removal, to permit relocation of Native Americans to reservations, to consolidate and compact reservation communities, to expedite westward expansion of the United States, and to protect Indian nations viewed as friendly or economically important to the United States.”

J. Diane Pearson, “Lewis Cass and the Politics of Disease,” Wicazo Sa Review, Autumn 2003, p. 9.

Considering this history, it is no wonder why many American Indian people today still distrust the federal government, and are among the first people to remind that government of its past.

That past, I should add, also and always gives meaning to the present.

Less than a year ago in November 2020, shortly after Pfizer announced “positive results” following its COVID-19 vaccine trial tests, Dr. Anthony Fauci exclaimed on ABC’s Good Morning America, “if you think of it metaphorically, the cavalry is coming here.”

His reference to the U.S. cavalry, however, did not sit well with some Native people who associated soldiers on horseback with destroyed Native lives, wrecked Indigenous communities, and even genocide.

For example, Regis Pecos, a member and former Governor of the Cochiti Pueblo Nation in New Mexico remarked to the Washington Post that “To Indian people, it signifies the beginning of a massacre. It references the threat of soldiers on horseback during the Indian Wars.”

Fauci’s reference also takes me back to the Hopi smallpox outbreak in 1899 when the federal government sent the cavalry, armed with Hotchkiss guns and other small arms, to the Hopi villages to force the people to comply with its health mandates.

Why?

Because the federal government was convinced that it knew what was best for the Hopi and other Indian people, and therefore believed it had good reason and the moral high ground to create and enforce its orders.

If only this form of paternalism existed with the federal government and only existed in the past. But it, too, is alive and well in our society and at the University of Arizona.

For several months, campus administrators have hosted weekly online briefings to update the UA community on their COVID mitigation efforts.

Week after week the message from President Robbins and Dr. Richard Carmona, a former Surgeon General and Washington bureaucrat, to campus is the same: mask up, social distance, and get vaccinated.

The briefings, while sometimes informative, reek of white privilege and paternalism.

Throughout my career, I have spent considerable time critiquing and pushing back against the idea and practice of white paternalism, especially as it relates to Native people.

Oftentimes, in my courses at UA and elsewhere I have lectured to my students on the racist attitudes of and the overt paternalism demonstrated by former U.S. presidents, including Andrew Jackson.

Known for forcefully removing (and killing) thousands of Indians from their lands in the Georgia and the Mississippi region, he viewed Indian people as children, and himself as their all-knowing, all trusting father, who always had their best interests in mind.

Take for example his letter to the “Cherokee Tribe of Indians East of the Mississippi” which he penned in March 1835, wherein he tells the Cherokee people that they have to leave their homelands in Georgia and move West:

“Listen to me, therefore as your fathers have listened, while I communicate to you my sentiments on the critical state of your affairs…I have no motive, my friends, to deceive you. I am sincerely desirous to promote your welfare. Listen to me, therefore, while I tell you that you cannot remain where you now are…You have but one remedy within your reach. And that is, to remove to the West and join your countrymen, who are already established there. And the sooner you do this, the sooner you will commence your career of improvement and prosperity…”

Andrew Jackson, March 16, 1835, Digital Public Library of America

While the President has a number of disturbing things to say to the Cherokee, we should be careful not to overlook this important point in his letter: The President’s one “remedy” for the Cherokee people was for them to obey.

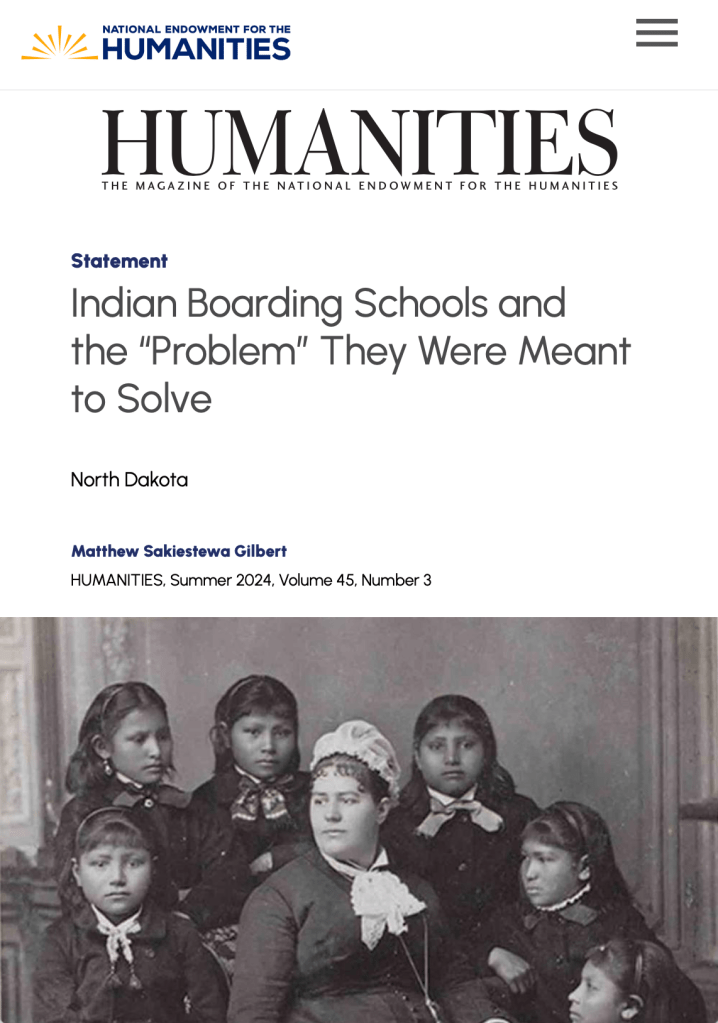

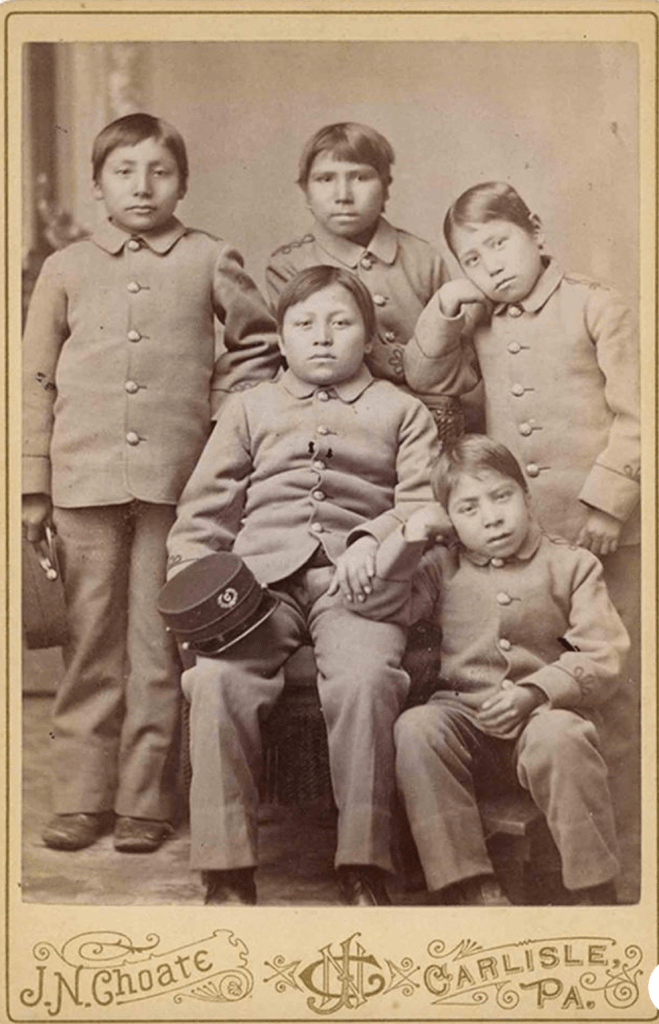

Years later, when government officials forced the great grandchildren of these Cherokees to attend one of 25 federal off-reservation Indian boarding schools throughout the United States, the practice of paternalism continued.

The federal government had created these institutions to assimilate Indian people into American society.

Oftentimes forcing Indian youth to attend these schools, government officials, including school superintendents, constructed them to operate similar to military forts, and urged their Indian pupils to first think of themselves as individuals (future U.S. citizens) and not as members of a tribal nation.

In this regard, they encouraged Indian youth to no longer listen to their parents, or rely on their culture or ceremonies to solve problems, including famines, droughts, and diseases.

Instead, they wanted Indian youth to believe that the federal government, personified in school officials, including matrons and teachers, had the answers to their problems and knew what was best for them.

While this history is rich, and I have certainly not done it justice here, I do want to move on and offer final comments about the present situation at UA before ending my talk today.

At the University of Arizona, I am fortunate this semester to be teaching a graduate course in AIS on Teaching College Methods. I have 6 students in the course. All but one are new to the university. All bright and engaging, and each dedicated to the field of American Indian Studies.

In this course, we spend considerable time talking about the foundational pillars of our field, including tribal sovereignty, nationhood, Native agency, self-determination, and decolonialism.

And they can attest, that week after week, I also encourage them, I urge them, to be critical thinkers. And I remind them that each of us, regardless if we are a student, faculty, or staff, are fortunate, and yes “privileged” to be studying and working at the University of Arizona.

“Your critical thinking should never stop,” I often tell my students, “regardless of the crisis, for this is the work that we do as scholars.”

Earlier this semester, during one of his COVID-19 weekly updates, President Robbins once again encouraged everyone occupying space inside a campus building to social distance and wear a mask.

Even admitting that the COVID-19 virus does not normally spread outdoors, he still encouraged everyone to wear a mask, noting that wearing a mask outdoors would help condition people to mask wearing, and would protect our faces from harmful rays of the sun.

“If wearing a mask is not about preventing the spread of the virus, then what exactly is it about?”, a question I asked my students.

For some Indigenous people, including myself, COVID masks are no longer about health, but have become symbols of colonization.

By colonization, I refer to when an outside force (usually a government) takes over, imposes laws, takes people’s land, dignity, agency, all meant to make everyone the same…to think the same, have the same language, practice the same religion, a new society structured on colonial norms… “the subjection of one people to another.”

In this regard, masks are indeed symbols of colonization, as they represent outside forces (the US government, county boards, governors, etc.) coming into our spaces (schools, classrooms, church buildings, parks, etc.), telling us what we can and cannot do, attempting to take away our dignity and agency, and wanting us to conform.

And let’s not forget that the goal of colonialism has always been to DOMINATE.

In the upcoming weeks and months campus administration at the University of Arizona will process hundreds of COVID-19 vaccine mandate exemption applications. Some they will accept, others they will reject.

For those who either refuse to comply with the mandate or whose exemption applications are rejected, what will happen to them?

We don’t know for sure. In previous statements and interviews, President Robbins has said that he is waiting on the Biden administration to give him and other campus administrators guidance on what to do with non-compliant employees or those without an approved exemption.

Will Robbins and other campus officials require them to undergo weekly COVID-19 testing at their expense? Will they not allow them to teach or work on campus? Will they decrease their salaries?

Perhaps he will simply fire them or force them to resign, Native people and Non-Native people alike. Those who have faithfully served this institution as excellent scholars, teachers, staff, and administrators. None of that may matter. What will matter is compliance.

Again, I remind you of my letter: “We know what is best for you. Obey us.”

Much more can and should be said about this topic, but at some point I need to start thinking about ending my talk, and this seems like a good place to do so.

The University of Arizona has one angry Indian on its hands. And this Indian happens to be the Head of its Department of American Indian Studies, a senior scholar of Native American history, and a member of an Indian nation in Arizona.

But this Indian also knows the value of working together to solve problems.

And so, I offer the following four recommendations to campus administration, which I hope they will consider:

First, keep your white privilege and paternalism in check. Stop using your positions of power in society and at UA to tell brown, black, and other white people what to do with their bodies. This is not a new mandate about academic excellence, it is about people’s health and a new experimental vaccine whose long-term effects have yet to be determined.

Second, take Native agency and self-determination seriously. Listen to us when we speak up and push back. If you are going to acknowledge our land, then you need to also acknowledge our right to Native agency and self-determination. To deny us these rights is to encourage and further colonialism on this campus.

Third, be understanding and compassionate with Native and non-Native people who choose not to comply or fail to secure an approved exemption to the COVID-19 vaccine mandate. You have already sent one of your Indian agents to the Native community at AU to urge us to comply or face consequences that could negatively affect our employment. As I told this individual recently:

“The University’s covid-19 vaccine mandate is an attack on Native agency and Indian self-determination. Urging Native people to comply with this mandate or face possible ‘consequences that could impact [our] employment,’ only perpetuates this problem and furthers fear among Indian people at UA. Now is the time that we need allies in our campus administration to fight for us, not threaten us.”

Matthew Sakiestewa Gilbert, personal email communication, October 28, 2021

Fourth, become less dependent on the federal government. Clearly, the timing of this vaccine mandate had little to do with health, and more to do with the threat of losing millions of dollars of federal funding. Because of the University’s dependence on federal monies, and failure to secure financial independence from Washington, people at UA will suffer, and some may even lose their jobs. That is not right.

I am happy now to take your questions or comments.

*****

Matthew Sakiestewa Gilbert (Hopi)

Professor and Head

Department of American Indian Studies

University of Arizona