Not many people who read this blog know that one of my hobbies is amateur (“ham”) radio. I’ve been a ham radio operator for almost 19 years. My interest in ham radio began when I was a kid.

In 1986, a couple named Marvin and Regina Goodfellow stayed a week with us in our home in Albuquerque, New Mexico. During the 1st night of their stay, Marvin asked me and my siblings if we would help him put up a large antenna in our backyard.

Later that night, Marvin (WA2FMD) set up a transceiver radio on our dining room table. He showed us how the radio worked. We listened to him talk to friends across the United States. He even let us talk on the radio. I remember having a conversation with someone from Los Angeles who worked at Disneyland.

When Marvin turned the dial on the radio, sounds became distorted and new sounds emerged. I heard people talking in Spanish and English, and I listened in wonder about the “dit” and “dah” sounds coming from the radio. Marvin told us that the sounds were called Morse code.

He showed us how to say our names in this new language, and we practiced that night on his Morse code key.

I was fascinated with everything having to do with amateur radio.

Six years later in the summer of 1992, I took the Federal Communication Commission written exam and 5 words per-minute Morse code competency test to receive the Novice class Amateur radio license. My first call sign was KB7QAW. After I upgraded my radio license, I chose the call sign WA7AZ.

Throughout my sophomore, junior, and senior year in high school, I spent hundreds of hours talking and “pounding brass” (sending Morse code) on my radio, which was a Kenwood TS-511s.

While many of my peers spent their free time playing video games, I was on the radio talking to people in the U.S., or places such as Hawaii, Colombia, New Zealand, Sweden, Mexico, and the Island of Aruba.

Today, I dusted off (literally) my Morse code key and brought out the radios to participate in the Amateur Radio Relay League Field Day event. Field Day is an annual contest where people operate their equipment from batteries charged by a solar panel or a gas generator. Some people simply use the power that comes from the outlets in their homes.

The idea behind the contest is to make contact and exchange information with as many operators within a specified 24 hour period.

At about 2:00 this afternoon, I “fired up” the radio on our backyard patio, pressed down on the mic, and called “CQ Field Day, CQ Field Day, CQ Field Day, this is Whiskey, Alpha, Seven, Alpha Zulu, Whiskey, Alpha, Seven, Alpha, Zulu, Field Day”

I waited a few seconds and then I heard a strong signal reply saying: “WA7AZ, this is Whiskey, Zero, Romeo, Romeo, Whiskey, Zero, Romeo, Romeo (W0RR).” The station was from Missouri, and within a matter of minutes I had made contact with people in Pennsylvania, Mississippi, Maine, Colorado, and Ohio.

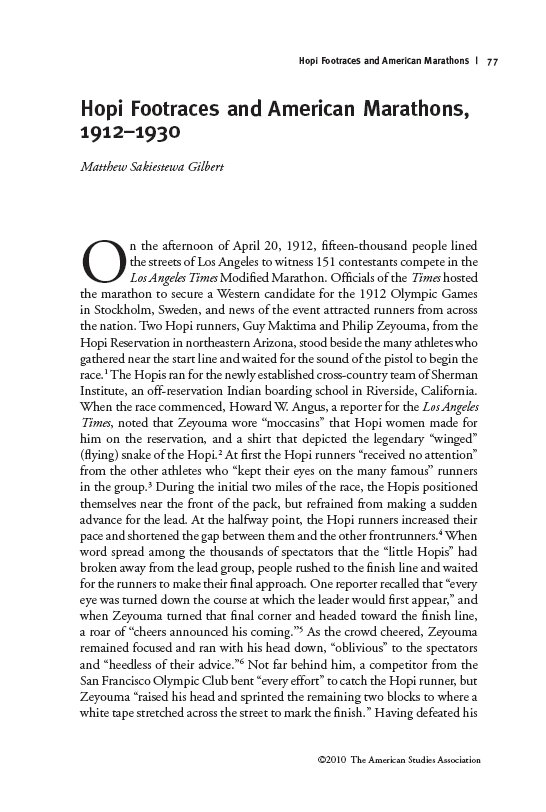

The above picture is of me talking to KT5J in Austin, Texas. My wife, Kylene, took this photograph for the blog. Nearly 10 years ago, I convinced her to get the Technician class amateur radio license.

Marvin passed away in 1998 at the age of 91. Just prior to his passing, I had my only QSO (radio conversation) with him. The QSO took place as I drove to Albuquerque from Flagstaff, Arizona. I don’t recall specific details about the conversation, but I know he was glad that I continued my interest in ham radio.

Matthew Sakiestewa Gilbert, WA7AZ