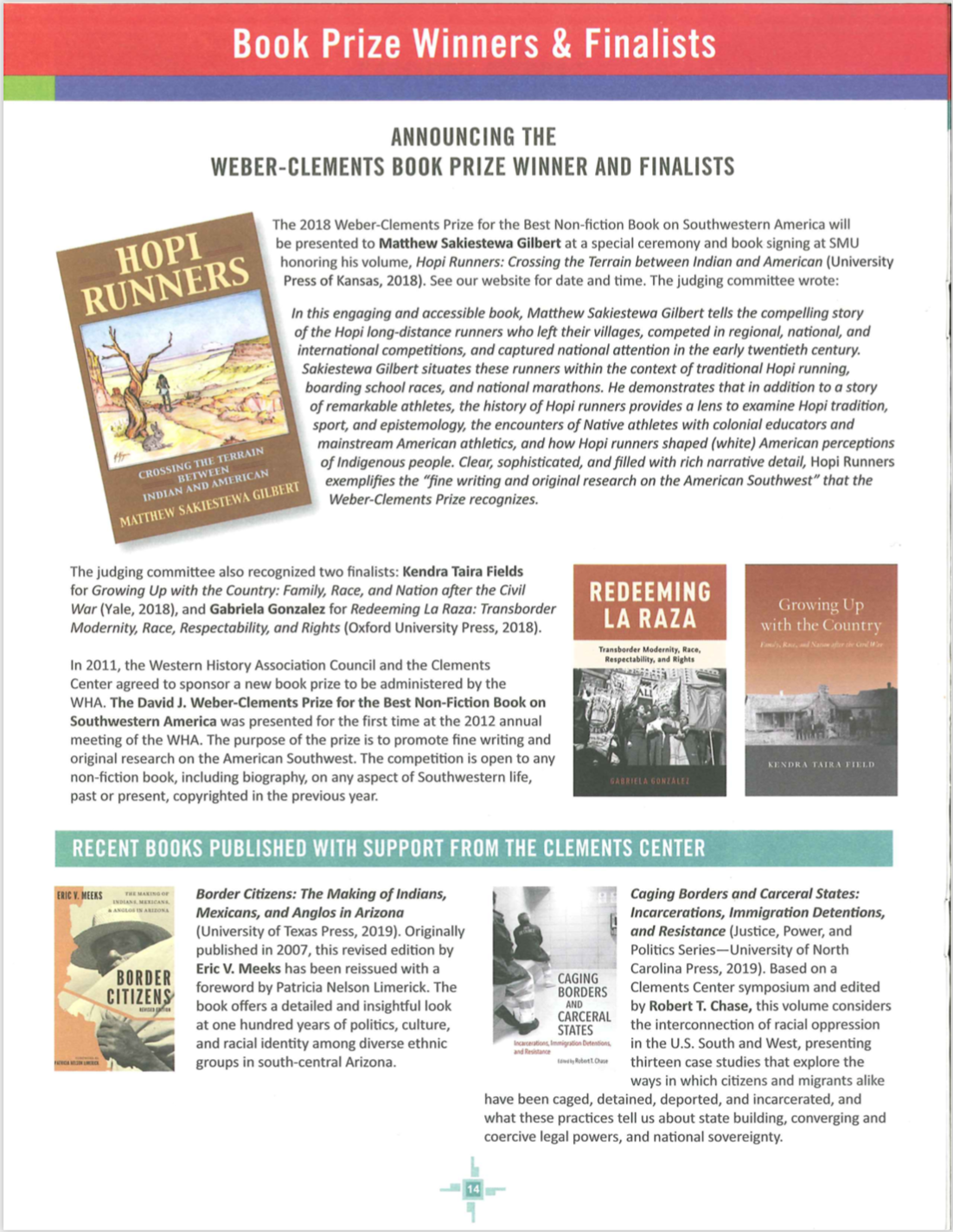

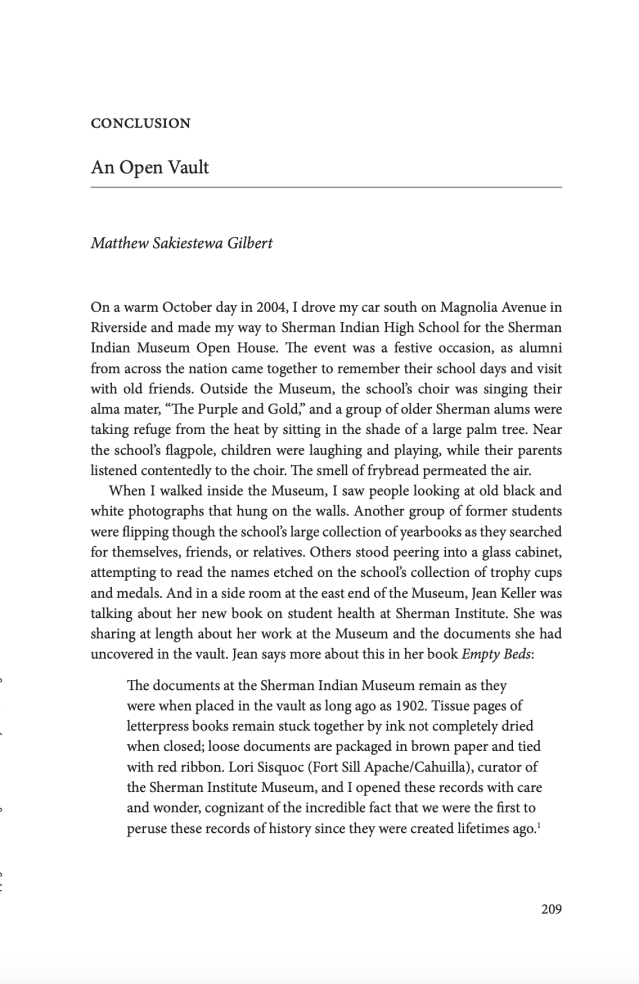

On September 30, 2025, the Center for Native American and Indigenous Futures (CNAIF) at Northern Arizona (NAU) invited me to screen Beyond the Mesas and say a few words before the screening. The event was part of CNAIF’s annual Orange Shirt Day to pay tribute to those who have been affected by the Indian boarding school experience. A special thanks to Sheena Hale, Director of the CNAIF, for this opportunity. Below is the text of my talk.

**************

Good afternoon, everyone,

Thank you for that kind and generous introduction.

It is such an honor to be here.

I have fond memories of Northern Arizona University.

When I was ten years old, my father, Willard Sakiestewa Gilbert (who is here today), accepted a faculty position in the College of Education as an Assistant Professor of Curriculum and Instruction. He remained at NAU for 32 years, retiring in 2019 at the age of 67.

Needless to say, I spent a lot of time on this campus, especially when I was younger. Running around the track at the old Athletic Center building, swimming laps at the Aquatic Center, and one time I even got the day off from school (I attended Flag High) to job shadow my father, learning all about what he did as a professor at NAU.

From an early age, my parents instilled in me an appreciation for education and a desire to pursue college beyond the mesas. I attended a small Christian school in Southern California called The Master’s College, now The Master’s University. And with the generous help of the Hopi Tribe Grants and Scholarship Program, I graduated in 1999, but my daughter, Hannah, also graduated from TMU earlier this year, and my other daughter, Meaghan, just started as a freshman there in August.

Any parent can tell you that sending your child away to school is not easy, especially when he or she is your first to go. You worry about their safety, whether they will quickly find good friends, who will care for them if they get sick, and a host of other things. And our children experience challenges, too. They often think of home, sometimes crying themselves to sleep (I know I did), missing their loved ones and longing for the day when they will be with their families. Life away from home can be full of uncertainties and insecurities, and yet (thankfully) it tends to get better over time.

As you are aware, the Hopi people, and I would add all Indian people, have a long history of having their children sent away to school, sometimes voluntarily, sometimes by force. Beginning in the late 1800s, the government began sending Hopi youth to off-reservation boarding schools in Albuquerque, Phoenix, and Riverside, to name a few. Most scholars who approach this topic interpret the Indian boarding school experience through federal Indian policies, including government attempts to assimilate them into American society. All are helpful and true, but there is another way of understanding it from an indigenous or Hopi perspective.

Ten or so years before he passed, the late Hopi historian Lomayumtewa C. Ishii described to me over lunch that the Hopi boarding school era was part of a second wave of Hopi migration. He reminded me that our clan people were once great travelers, traveling west to the Pacific Ocean, north into present-day Colorado, east into New Mexico, and far south into Central America.

And it was the late Ferrell Secakuku, while pursuing a Master of Science degree in anthropology at NAU, who taught me how these ancient travelers learned from their experiences, met other indigenous people on their journeys, and took that knowledge back to their ancestral lands to form the essence of Hopi society. In this regard, beginning in the late 1800s, the Hopi people once again ventured beyond the mesas, traveling to schools to receive an education, experience life away from home, and return to their villages with skills that were supposed to be useful to their communities.

While Hopi students returned to the reservation with new skills, many remained unlearned in some Hopi ways and customs back home due to being away at school. Students often stayed three years or more at off-reservation Indian boarding schools without returning home. Absent from home, Hopi students at Indian schools did not participate in various religious ceremonies and other cultural events throughout the year. This affected not only the students themselves but also their children.

Hence, the negative consequences of being away from home had a generational effect on the Hopi people. Lois Pooyouma, a Hopi student at Sherman Institute in the 1970s, remarked in the film: “I missed out…I never learned really how to do piki. I didn’t know really too much about Hopi weddings. I don’t remember being initiated and doing what these kids are doing now because I was gone. So that was the bad part about being in a boarding school that you didn’t learn what you were supposed to learn as you were growing up. And therefore I couldn’t really teach my daughter what she should do, and I think in a lot of ways we are both learning, or all of us are learning.”

Far from home for long periods of time, Lois and other Hopi students “missed out” on receiving a Hopi education in their homes and village communities. Instead of learning Hopi ways and customs and a worldview according to Hopi understandings, they learned about the superiority of Western society. In this regard, while they returned to the Hopi mesas as stronger American citizens, they came home as weaker Hopi individuals. And weaker individuals who lacked Hopi knowledge and skills made for a weaker Hopi society.

Perhaps the most detrimental consequence of being away from home, and one that had the longest negative effect on Hopi society, was that the off-reservation Indian boarding schools, including Catholic mission schools, did not teach Hopi youth to become good parents. Separated from their mothers and fathers, Hopi students received instruction and discipline from their teachers, matrons, and other school officials, including Catholic nuns.

Although they each took a parental role in the lives of Hopi youth, they did not parent them according to Hopi ways. Nor did they show love, instill confidence, or counsel them, including how to solve life’s problems, according to Hopi customs. As former Hopi Tribe Chairman Ivan Sidney noted in the film: “Being raised in the boarding school really did not teach us parenting, and some of that is carried on when we became parents. I know for a long time I had a difficult time telling my children that I love them and supporting their school because nobody ever said that to me.”

Sidney’s observation that boarding schools did not make for good parents is important for several reasons. In Hopi culture, parents are responsible for teaching and nurturing their children. They are responsible for preparing their children to learn knowledge and skills that will best prepare them for success on and beyond the mesas. The adolescent and later teenage years are challenging for young people. Becoming young adults and the hormonal and physical changes that come with it, older youth often struggle with anxiety, depression, and a lack of confidence.

In Hopi society, parents are supposed to be present for their children during these difficult and impressionable years; there to give counsel, instruction, and comfort during life’s hardships. And parents and other family members are to be there to instill in their children assurance of Hopi ways and confidence in their identity as clan and village members.

Instead, at boarding schools, officials wanted Hopi and other Indian students to see their cultures (and even their parents) as hindrances to their success. They did not provide Hopi youth with what they desperately needed, that is, parenting according to Hopi ways and customs. Instead, they modeled parenting from Western perspectives, which left the youth confused and feeling inadequate to parent their children on the reservation.

Perhaps, your very own Professor Alisse Ali-Joseph and Kelly McCue, in their insightful chapter in Indigenous Justice and Gender, said it best: “While boarding schools were the most prominent site of assimilation, policies outside of these schools further functioned to isolate youth from their families and communities. These policies left children without their mothers, traumatized by the horrific sexual, physical and emotional abuses they endured, and mothers without children, leading to generations of depression, substance use, domestic violence, and the inability to parent.”

I want to close my comments by retelling a story about an experience I had filming Beyond the Mesas, which speaks to the reason why I, and others, including the Hopi Cultural Preservation Office, produced this film.

Over the years, I often said that the “star” of the film was Marsah Balenquah from the Village of Paaqavi. Although I have written at length about Marsah in the Journal of American Indian Education, I thought I would close my talk this afternoon with her story, as a way to honor her memory and remind us of the sacrifices she and others made to get us where we are today.

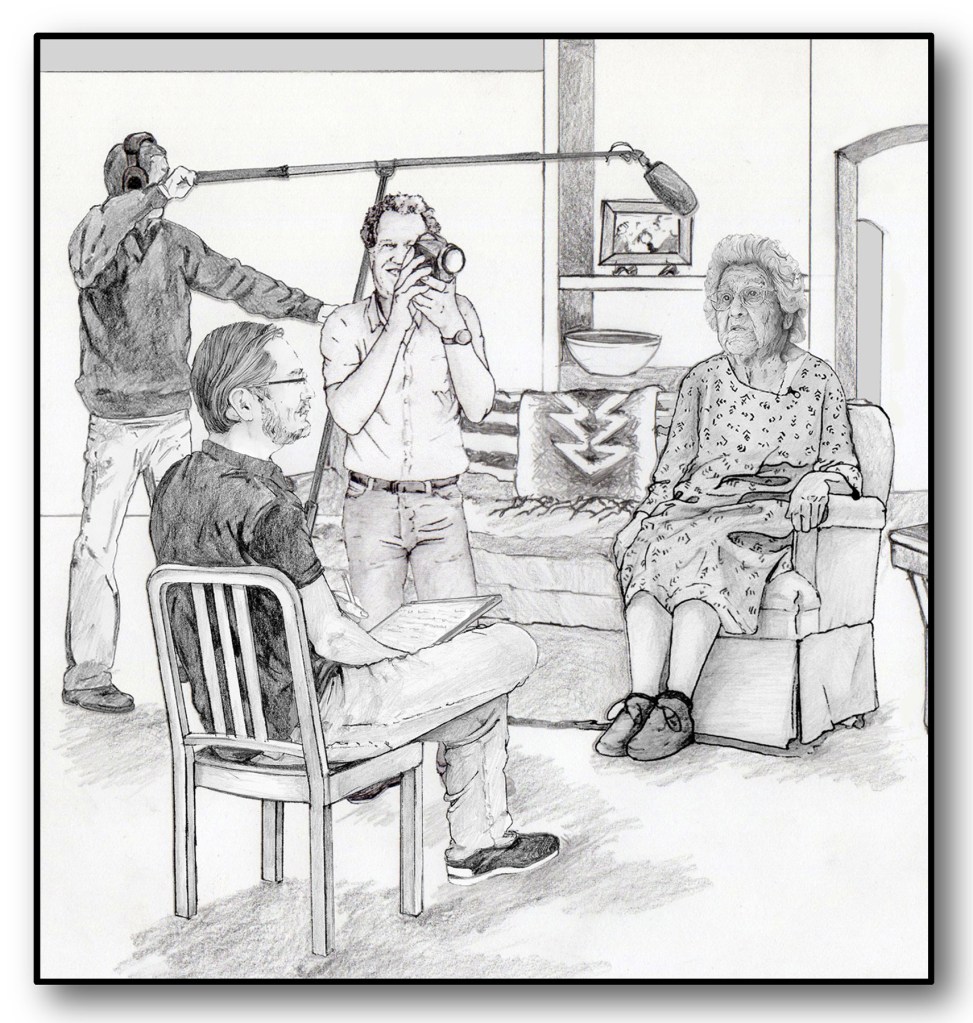

To film Beyond the Mesas, I, along with a small crew from 716 Productions, spent nearly a week at Hopi meeting individuals and talking with former boarding school students. Although we interviewed a number of people during that trip, an interview with Marsah will always remain special to me. We had been interviewing Eileen Randolph from the village of Bacavi, and her granddaughter, Leslie Robledo.

We spoke at length about Eileen’s mother, Bessie Humetewa, and her experience at Sherman during the 1920s (two years earlier, I interviewed Bessie, but shortly before this second visit she passed away). During their interview, Eileen and Leslie kept referring to a woman named Marsah Balenquah from the same village, who attended Sherman with Bessie. Even though my grandmother once told me about Marsah and how we are related, I had never met her. “She lives right across the road,” Eileen said to me, “you should interview her!” With their help, we made plans to visit Marsah at her home the next day.

When we arrived at the house, an elderly woman wearing an apron greeted me at the door, somewhat bewildered why I was standing on her porch. After telling her my name, I told her the reason for my unannounced visit. I explained that Eileen and Leslie had suggested that I interview her for my film on the Hopi boarding school experience. “Oh,” she said to me, “come in, come in.” She gestured for me to sit down on the couch, while she quickly prepared traditional Hopi tea for us called Hohoysi on her gas stove.

As we waited for the tea to brew, I told her that my So’oh (grandmother) Ethel from Upper Munqapi had sent her greetings. “I know Ethel” she exclaimed, “we are related to each other!” “Yes,” I said to her, glad and relieved that in determining Marsah’s familial connection to my grandmother, my family and clan connection to Marsah had also been established.

When our tea was ready, Marsah sat down next to me on the couch and immediately began telling about her school days at Sherman Institute. We must have talked for thirty minutes, all the while the film crew waited patiently outside. At one point in our conversation, Marsah recalled the first time she felt an earthquake. She explained that it was a frightening experience for all of the Hopi kids at Sherman, and she described how the walls in her dorm swayed back and forth until the quake stopped.

“Marsah,” I said to her, “I want to hear more about this and your other experiences at Sherman, but I need you to tell me these stories on camera. We cannot include your stories in our film if we are not able to record them.” The moment I said, “camera,” Marsah’s countenance and behavior changed. “I don’t want to do it,” she said to me, “I don’t want to be on camera.”

Marsah lived in a small village community. Perhaps worried about village gossip, or bashful of her story, she was reluctant to draw unnecessary attention to herself. I did not know how to respond. The last thing I wanted to do was make her feel uncomfortable. I respected her wishes, and her right to privacy, but maybe there was something I could say that would ease her mind? Perhaps I could help her see the situation and opportunity from a different, less threatening perspective?

I continued thinking about this as we finished our conversation, but no words or persuasive arguments came to mind. After we finished our tea, I collected my notes and headed toward the front door. Feeling somewhat hopeless and disappointed, I turned and asked one last question. “Have you ever told your children or grandchildren these stories about your school days?” She did not respond. “If you allow us to film you,” I said to her, “your family will have these stories forever.” She took five or so seconds to consider my words, and then she said, “Okay, I’ll do it.”

I think we would all agree that we are so thankful that she did.

Kwa-kwa

on the Hopi Reservation in northeastern Arizona. His willingness to receive an education beyond the mesas and teach at a university, paved the way for other Hopi academics such as myself. He showed us how to excel at a research institution. And he demonstrated the importance for us to meet scholarly expectations while remaining closely connected to home.

on the Hopi Reservation in northeastern Arizona. His willingness to receive an education beyond the mesas and teach at a university, paved the way for other Hopi academics such as myself. He showed us how to excel at a research institution. And he demonstrated the importance for us to meet scholarly expectations while remaining closely connected to home.