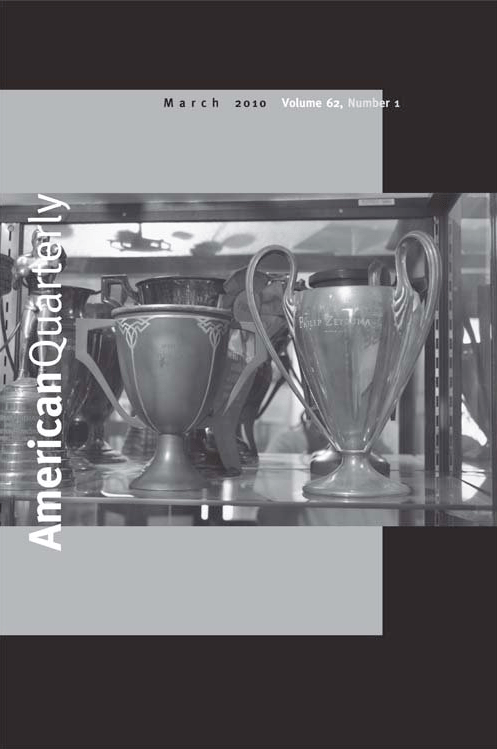

For the past three years I have been working on a book on Hopi long distance runners and the American sport republic. Part of this project includes an article that I wrote titled “Hopi Footraces and American Marathons, 1912-1930.” This article recently appeared in the March 2010 Issue of American Quarterly (Vol. 62, No. 1, pp. 77-101). The American Quarterly is the flagship journal of the American Studies Association.

The photograph featured on the cover of the journal (pictured above) is of two trophy cups that Hopi runner Philip Zeyouma won at Sherman Institute. I took this photo at the Sherman Indian Museum in Riverside, California. Not long after the school established its cross-country team, Zeyouma won the Los Angeles Times Modified Marathon in April 1912. His victory also gave him an opportunity to compete in the 1912 Olympic Games in Stockholm, Sweden.

When Hopis such as Zeyouma, Harry Chaca, Guy Maktima and Franklin Suhu competed on the Sherman cross-country team, and Louis Tewanima ran for the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, their cultural identities challenged white American perceptions of modernity and placed them in a context that had national and international dimensions. These dimensions linked Hopi runners to other athletes from different parts of the world, including Ireland and Japan, and they caused non-Natives to reevaluate their understandings of sports, nationhood, and the cultures of American Indian people.

This article is also a story about Hopi agency, and the complex and various ways Hopi runners navigated between tribal dynamics, school loyalties, and a country that closely associated sports with U.S. nationalism. It calls attention to certain cultural philosophies of running that connected Hopi runners to their village communities, and the internal and external forces that strained these ties when Hopis competed in national and international running events.

The back cover of the journal (pictured below) features a photograph that I took on the edge of Third Mesa near the village of Orayvi. At one point in the article I describe how one can stand in this location and see for miles in all directions:

To the south, the land extends beyond the Hopi mesas and the silhouette of Nuvatukiyaovi, or the San Francisco Peaks, is visible in the distance. In the valleys below, corn, melon, and bean fields stand out as green patches against a backdrop of earth and sandstone. From on top of the mesa one can enjoy the sweet smell of burning cedar, hear and feel the wind blowing over the mesa edge, and behold a breathtaking landscape surrounded by a canopy of deep blue sky. Looking east toward the village of Shungopavi on Second Mesa, running trails stretch from Orayvi like veins that connect and bring life to each of the Hopi villages. The trails near Orayvi give testimony to the tradition of running in Hopi culture and the continuance of running among today’s Hopi people. [p. 79]

I am indebted to several individuals who helped me revise this essay, including my colleagues at the University of Illinois, various Hopi and non-Hopi scholars, the Hopi Cultural Preservation Office, Lorene Sisquoc of the Sherman Indian Museum, and American Quarterly editors Curtis Marez, Jeb Middlebrook and Stacey Lynn.

If you would like a PDF copy of this article, please feel free to email me at sakiestewa@gmail.com, or submit a comment to this post.

Matthew Sakiestewa Gilbert

See also BEYOND THE MESAS post: Hopi runners article available for download