On September 1st I traveled back home to deliver a talk on Louis Tewanima at the Louis Tewanima Footrace Pre-Race Dinner. A reporter for the Navajo Times named Cindy Yurth was present in the audience, and recently published a story about the gathering. A special thanks to Yurth for granting me permission to republish her article on my blog.

————————————–

Tracking Tewanima

Centennial footrace draws record crowd to mesas

By CIndy Yurth

Tséyi’ Bureau

SHUNGOPOVI, Ariz. — Louis Tewanima may be the most celebrated Hopi runner, but he himself would have admitted he was not the fastest, a Hopi historian told the crowd gathered Saturday night for a celebration of the centennial of Tewanima’s bringing home an Olympic silver medal to this tiny but spectacular hamlet on top of Second Mesa.

The fastest Hopi ever was probably some unheralded farmer who never had a chance to go to school — or was forced to, as Tewanima was.

Still, Tewanima was the one who brought home the medal, and this past weekend Hopis along with well-wishers from around the world celebrated the centennial of that feat with footraces of varying lengths along some of the very trails Tewanima himself once graced.

“It was great to follow in his footsteps,” said the second-place finisher in the commemorative 10K race, 16-year-old Kyle Sumatzkuku of Moencopi and Mishongnovi. “I look up to him, even though he was even smaller than me.”

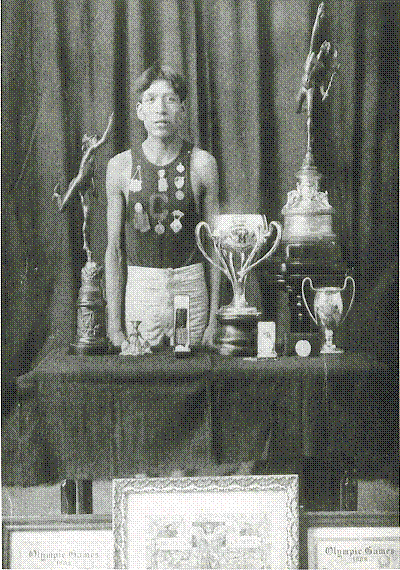

Sumatzkuku is not a large person by any means, but he’s probably correct in assuming Tewanima was smaller. Tewanima was 5-foot-4 1/2 and 115 pounds, according to Illinois University Professor Matthew Sakiestewa Gilbert, who gave the historical address Saturday night. In the press of his day, he was referred to as “the little Hopi redskin.”

This past weekend, though, he was everywhere. Perhaps literally.

“We believe they (the spirits of the departed) come to us in the clouds,” said race announcer Bruce Talawyma. “So he’s all around us today.”

Somewhere else, in fact, the race might have been cancelled when a torrential downpour washed out part of the trail Saturday. But Hopis, those ultimate dry farmers, know better than to scoff at moisture, even when it comes at such an inopportune time.

“That’s what we’re running for, right?” asked Sam Taylor, Tewanima’s great-nephew and one of the organizers of the race, at the pre-race carb-loading party that featured both the traditional spaghetti and a Korean noodle dish, courtesy of a Second-Mesa war bride and her churchmates. That’s a whole ‘nother story.

Running for rain was certainly the rule in Tewanima’s time. As a member of the Sand Clan, Gilbert explained, Tewanima and his kinsmen were charged with running to far away places and back to “bring back the rain.”

That could be part of why Tewanima offered to run for Carlisle Indian School even though he was dragged to the school after protesting Natives being forced to study at Western institutions — and how he ultimately ended up in the Olympics.

As for the history of the Louis Tewanima race itself, it was mostly started because the organizers — the Hopi Athletic Association — saw the need for a competitive footrace on Hopi to give Hopi runners a goal. Naming it after Tewanima was almost an afterthought, said Leigh Kuwanwisiwma, who helped organize the first Tewanima Footrace in 1972.

“I’m not really sure how Louis Tewanima was brought into it,” Kuwanwisiwma confessed.

One sure thing is that the race succeeded in bringing attention to Tewanima’s feat, which may have been nearly forgotten otherwise.

“Everybody knew Louis Tewanima, just like we know everyone in the village,” explained race volunteer Kathy Swimmer of Shungopovi. “When I was growing up, him and his wife used to sit on their front porch in the morning and watch the kids load into the school bus. We just thought they were a nice old couple. I had no idea he was an Olympian until I joined the high school booster club and started helping with the race.”

After winning the silver medal, Tewanima returned to Shungopovi and never ran again except for religious reasons and pleasure.

As Gilbert mentioned in his talk, Tewanima himself knew he was not the fastest Hopi and never had been.

In the course of his research for a book on Hopi running he plans to publish soon, Gilbert uncovered a tale that he thinks sheds some light on the Tewanima era.

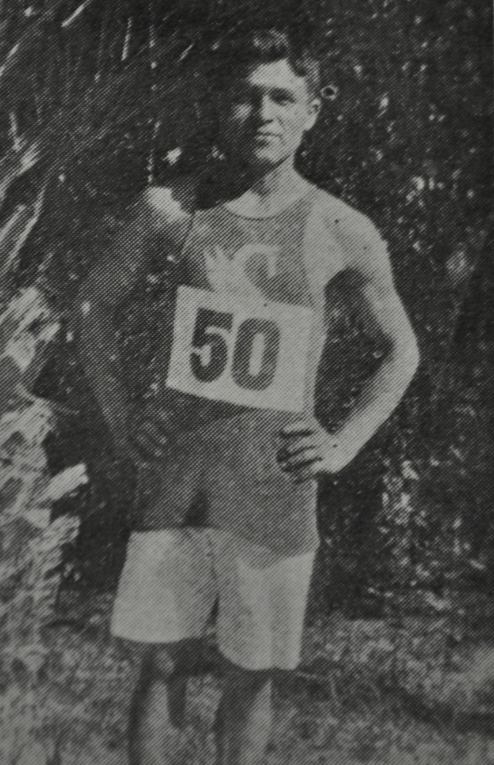

Apparently, Tewanima and fellow Hopi track star Philip Zeyouma, who attended Sherman Institute, were both home for a break and people encouraged them to race each other to prove once and for all which man was the best runner.

As both men appeared on the starting line in their school-issue tracksuits, the older men of the village started teasing them.

“You don’t look much like Hopi runners,” taunted one man.

“If you think you can do better, then come and show us!” challenged Tewanima.

Two 50-year-old men stepped forward.

“According to the New York Times report, they had essentially no clothes on, no shoes on, and looked like they were dying of consumption,” Gilbert said.

However, “By the time they reached the six-mile mark, those older men were so far ahead that Louis Tewanima and Philip Zeyouma dropped out of the race.”

The two 50-year-olds crossed the finish line “and just kept going,” Gilbert said.

So neither Tewanima nor Zeyouma was the fastest Hopi. And yet, Gilbert argued, they deserve to be honored, particularly Tewanima.

“This new generation of Hopi runners represented a transition in Hopi running,” the historian said.

“Whereas before people ran for transportation, and for religious reasons,” Gilbert said, “Tewanima ran as an ambassador of his people. He used running to create a privileged condition for himself at the Indian school. He used running to broaden his experience of the world.”

And as for the Louis Tewanima Footrace, “it gives testimony to the importance of running in Hopi society,” Gilbert said. “It celebrates the continuity of Hopi running.”

A record crowd of 361 runners would seem to agree.

————————————–